Latin American Gothic

Barbara Burns talks to Jenny Haase and Joanna Neilly, whose book German Romanticism and Latin America: New Connections in World Literature appeared recently in Legenda’s Transcript series.

BB. The title of your newly published volume, German Romanticism and Latin America, opens a window on literary-cultural connections that are not well known to most readers. Can you tell us in a nutshell what your book is about?

JN. I’m not sure I can make it quite a nutshell! But the book takes an unusual point of comparison – German philosophy, literature, art, and culture from the early nineteenth century on the one hand; and recent Latin American fiction and cultural production on the other.

While the Romantic period is also the age of empire and colonialism – and Alexander von Humboldt was of course only able to explore Latin America under the aegis of the Spanish Empire – there are nonetheless signs of cross-cultural connections and two-way influences between nineteenth-century Germany and the Latin America of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries that are not so marked by power imbalances. For example, the idea of nationhood and identity is crucial in both cases, as Germany emerges from Napoleonic occupation and as Latin American countries – former colonies of Spain – gain their independence.

But beyond the political, there are clear aesthetic resonances that kept surprising us, between authors from strikingly different backgrounds and times. So, for example, experimental formal styles, fragmentary writing, the emergence of the Gothic to question familial and political norms, fears about a growing popular market undercutting the aesthetic value of literature and art – these are all aspects explored by the authors considered in our book. And so we set out to think about reception and influence in a new way: how can two such diverse cultures and times have so much common ground?

The book maps the actual historical-cultural connections established in the nineteenth century by Germans in Latin America, via travel, translation, and criticism. But it also shows how a range of South American authors have determined their own literary aesthetic, by engaging with but also critiquing and resisting the cultural influences that arrived in the sub-continent during the Age of Empire.

BB. The famous German Romantic-era explorer and scientist Alexander von Humboldt is a towering figure in this debate because he wrote extensively about his travels across Latin America. But does his nineteenth-century imperial context also make his legacy slightly problematic in terms of mediation of knowledge about this part of the world?

JN. Absolutely – and a chapter in the book looks at recent critical responses to Humboldt’s legacy by Latin American writers and experimental artists. Alexander von Humboldt has been credited as the ‘second discoverer’ of Latin America. He travelled widely in the Americas between 1799 and 1804 and wrote up his vast scientific findings. He produced much of the scientific knowledge of the region that was imported back to Europe: to take just one example, charting the course of the Orinoco River to establish its source. But he was not just a scientist – he had an artistic perspective on the world he discovered and wanted to convey a sense of the interconnections within nature and indeed, of all disciplines. In this sense he is truly a Romantic, because he is interested in transcendence instead of particulars – not for nothing is his masterwork called ‘Cosmos’.

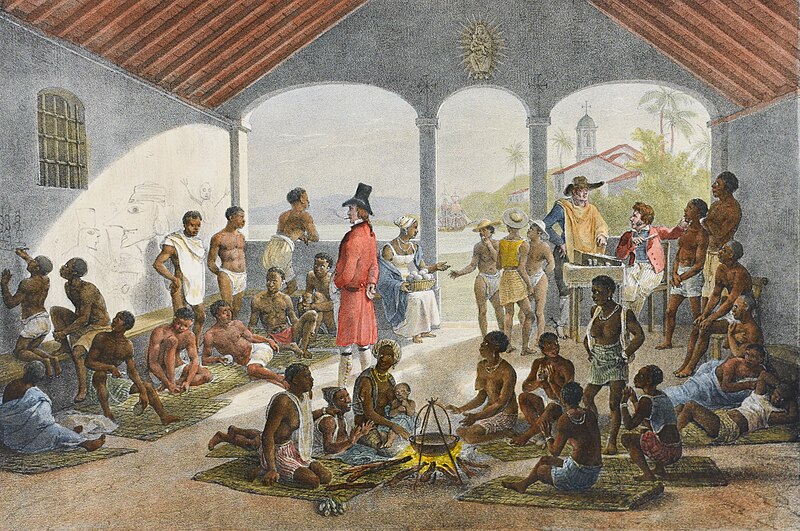

Humboldt also encouraged artists from Europe to follow in his wake, as he hoped to see the places he had uncovered in such scientific detail, also represented in art. One such artist was the German Johann Moritz Rugendas, still considered a canonical painter of the nineteenth century in many Latin American countries today. Humboldt saw him as a kind of protégé. But naturally there are problems here too – Latin America starts to become something exotic, to be marketed to Europeans back home, keen for the sensational adventure stories of travel into the unknown. Humboldt himself was no enthusiastic proponent of empire, but he did help to create this market. It was therefore important to us to show how his legacy is highly valuable, but also that what it represents – whether he meant it to or not – has also been critiqued in post-colonial writing.

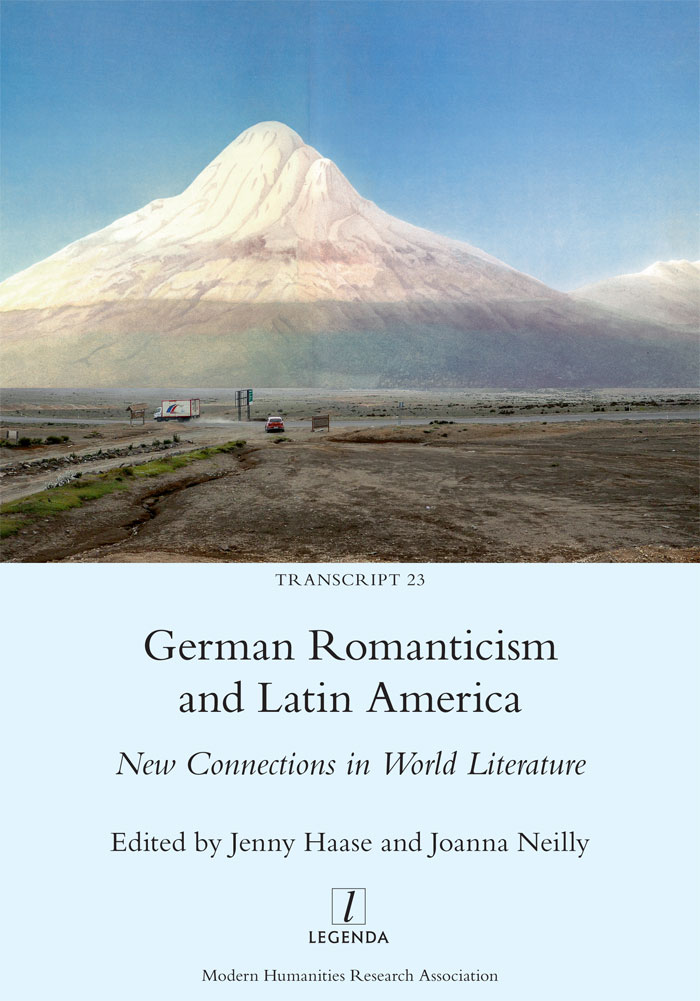

The cover of our book, an image by the photographer Alexander Glandien, gives a taste of this critique. It merges Humboldt’s representation of the Chimborazo in Ecuador with a present-day photograph from the exact same spot, and so reminds us that images of the region can never be static and essentialized.

BB. How did the two of you meet and end up working together on this edited volume?

JH. We met by an awesome coincidence: we ended up next to each other in a pub at the annual conference of the American Comparative Literature Association (ACLA) in Harvard in 2016. When I asked Joanna what she had talked about in her presentation, she replied: ‘Oh, about some Latin American novel set in Germany during the Romantic period that nobody in German Studies seems to know...’. I asked her if she meant Traveler of the Century by the Argentinean author Andrés Neuman, which was indeed the case. I myself had recently published an article about the novel as well, so that’s how we started talking. We subsequently presented a joint paper at the following ACLA conference in Amsterdam. And then our shared interests in Latin American-German connections gave rise to the idea of a joint international workshop.

JN. It really was one of those serendipitous moments! And I think it’s also fair to say, then, that the whole project really began with our joint enthusiasm for Andrés Neuman. So we are incredibly pleased that Andrés himself agreed to be part of our project.

BB. Is our exposure to Latin American literature in the West influenced to some degree by publishers’ choices regarding topics or literary styles that can be marketed to a global readership, and is this a factor which your study examines?

JH. Yes, absolutely, the global book market, commercialization and marketing are central to the reception of Latin American literature in Europe and the USA and have also been a topic of critical Latin American research for some time. The most prominent example here is that of magical realism and the boom in Latin American literature in the 1960s and 70s, which is closely linked to exoticization, othering, and the thematic focus on continental and national identity issues. In this context, I find it significant that a novel such as Traveler of the Century (2009) by Andrés Neuman, which is set in Germany during the Restoration period and which won the prestigious Alfaguara Prize and has been translated into numerous languages, has not yet been translated into German.

A current phenomenon in globally distributed Latin American literature is the ‘New Latin American (Female) Gothic’. Writers from the Cono Sur and the Andean countries of Ecuador and Bolivia, in particular, are marketed under this label. They deal with contemporary political and social conflicts and dynamics of violence in Latin America from a locally situated perspective and with the aesthetic strategies of the fantastic or horror.

BB. Your book introduces us to a range of twenty-first-century Latin American authors whose work engages with German themes. What kind of topics do they address?

JH. It’s fascinating to see how many Latin American writers have reached out to German history and culture of the ‘long nineteenth century’ in recent years. A very recent example is the novel Austral (2022) by the Costa Rican author Carlos Fonseca. Among other narrative threads, he follows the traces of a German anthropologist in the Amazon region and those of Nietzsche’s sister Elisabeth in the proto-fascist colony ‘Nueva Germania’ in Paraguay.

The subject of National Socialism was also present in Latin American literature from an early stage (for example, in Jorge Luis Borges’ ‘German Requiem’ (1946)). Jorge Volpi (Mexico) has fictionalized the topic for a wide audience with his game of hide-and-seek about an ominous German scientist in In Search of Klingsor (1999). The famous Chilean author Roberto Bolaño can be considered the author who has most succinctly expressed the duality of horror and fascination with German culture in many of his novels, especially in the posthumously published 2666 (2004), in which Nazi history and references to German literature go hand in hand in a disturbing way. An explicit focus on the confrontation with fascism can be found in the fictional compendium Nazi Literature in the Americas (1996) and the novel The Third Reich (2010).

Another major focus is on the political, historical, and cultural role of Germany and its role as an ‘informal empire’ in nineteenth-century Latin America.

BB. Is there a key insight that forms a common thread running through this collection of essays?

JN. Interestingly, in the workshop we kept coming back to the problem of the capitalist market. I think the question of aesthetic autonomy and its inevitable entanglement in the market remains key, especially now, as we think of world literature as something utopian, but which is evidently subject to marketing, to the creation of marketable images for an ever-widening readership. This question of capitalism and its dual face – the market both democratizes and excludes – seems particularly relevant when we think of the tangled relationship between a former imperial power, and a region in which it had informal imperial connections; when we think of the Latin American search for cultural identity post-empire, and of the marketization of this identity within Europe.

Luckily, we also find pockets of resistance to easily-marketable images in both the German Romantic and the contemporary South American context – via challenging and productive new aesthetic forms and of course via surprising new world literary relations. Authors we may have forgotten are suddenly revived in contemporary fiction for critical impetus. All of which is to say, in brief, when it comes to the Latin American reception of German Romanticism, and particularly perhaps in Roberto Bolaño, Andrés Neuman and César Aira, expect the unexpected!

BB. Did the process of preparing this volume change your perspective on contemporary academic discussions about world literature, or about Eurocentric world literature models?

JN. I was particularly inspired by the concept of ‘horizontal’ relations, or what Emily Sun has referred to in her 2021 book as ‘the horizon of world literature’. Sun looks at Romantic-era England and Republican-era China, almost one hundred years on; she was in turn inspired by Ning Ma, whose 2017 study The Age of Silver looks at realism not as a literary movement with a clear temporal and geographical source, but rather as having multiple beginnings in different times and places nonetheless experiencing similar cultural changes.

I also like Alexander Beecroft’s concept of ‘literary ecologies’, a term taken from environmental studies but applied to show how similar conditions – a cultural or political ‘climate’ as it were – in disparate places can produce literary affinities. This seemed to be a way of getting away from the persistent but problematic idea of one culture influencing anther – particularly in a post-colonial context – and instead helped me to think about how cultural affinities can arise that are not necessarily about one-way cultural transfer. I am increasingly thinking of Romanticism less as a literary movement and more as a mode of writing – which is not to say that it is divorced from historical context, but that its form and expression are ways of responding to or resisting certain cultural conditions – like the market, like nationalism, and so on.

BB. Do you still teach German Romantic texts as part of the undergraduate curriculum? If so, which authors work well?

JN. Some Romantic authors seem to translate better than others to undergraduate syllabi today. E.T.A. Hoffmann remains a firm favourite, and is pretty popular – as far as nineteenth century authors go – with students today; Heinrich von Kleist is also very rewarding to teach as his extremes of emotion and radical subject matter – an unwed pregnant woman advertising in the newspapers to find the father of her baby! – allows students to see that the nineteenth century is not some dusty, remote place.

Kleist of course also deals with the topic of empire – in Haiti, in Chile – as does Hoffmann, less obviously, but his depictions of Poland for example demonstrate what Kristin Kopp has shown to be Germany’s ‘colonial’ treatment of the Eastern outposts, at a time when Poland was partitioned. Gender is of course an important aspect to consider too – I try to include Bettina von Arnim, and Karoline von Günderrode – but also to look at how Romantic writers constructed and critiqued gender ideals, whether through satires on the bourgeois marriage market or self-reflexive comments on how the female muse can be so dreadfully abused and taken for granted by the male artist. A man falling deeply in love with an automaton, as happens in Hoffmann’s The Sandman, is hardly irrelevant in our age of advanced A.I. And of course, a bit of horror always sells! Ludwig Tieck is probably the master here.

Students always bring new perspectives. They find parts of these stories that surprise, delight, or provoke them, and we can go from there.

full news feed • subscribe via RSS