Christoph and Caesar

Barbara Burns interviews Christoph Pretzer, whose book Writing Across Time in the Twelfth Century: Historical Distance and Difference in the Kaiserchronik has just appeared as volume 25 in Legenda's Germanic Literatures series.

BB. How did your interest in medieval studies begin?

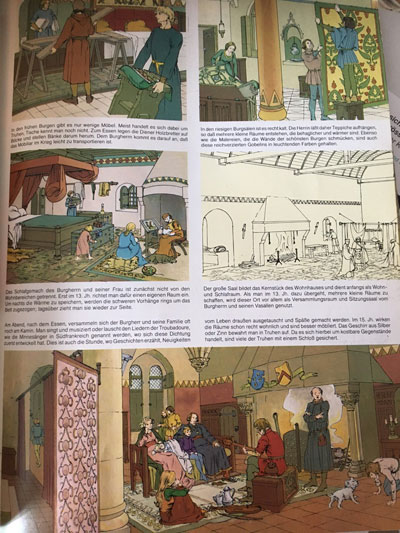

CP. My parents are squarely to blame for this. For my seventh birthday they gave me a huge book: ‘This is How they Lived in the Middle Ages, the Times of Castles and Knights’ (this is my English translation of the title, though the German book I have is based on a French original, very much like a medieval knightly romance). The book combines vibrant pictures of medieval life, people and events with short explanatory texts, and prompted my early fascination with all things medieval. I excavated it from an old box during a recent move and it now has pride of place on my research bookshelf. Flipping through its pages again now, I remember how the pictures, in a 1970s Franco-Belgian bande dessinée style, really appealed to me, and how I was intrigued by the way the book manages to convey a sense of the Middle Ages as a thousand years of hugely diverse and complex history!

BB. What brought you from Germany to Cambridge for your PhD?

CP. I ended up at Cambridge entirely by accident. Towards the end of my MA in Bamberg, I started looking for PhD positions. I didn’t have much success at first, but then I stumbled across an advert for a PhD-studentship at Cambridge that matched my profile so well it was almost comical. Going to a university like Cambridge had never been on my priority list, as I am very much a proponent of the German model of egalitarian and comprehensive access to higher education. But I had always wanted to spend some time in Britain, and English literature, films, and music had been an important part of my life, so I jumped at the chance to apply and miraculously got the position.

BB. Your book focuses on the Kaiserchronik, which is a classic text of medieval literature, a record of the Roman and German emperors and kings from the establishment of Rome until the twelfth century, written in the vernacular. Why is this such an important chronicle? Was it the first example of popular history for non-specialists?

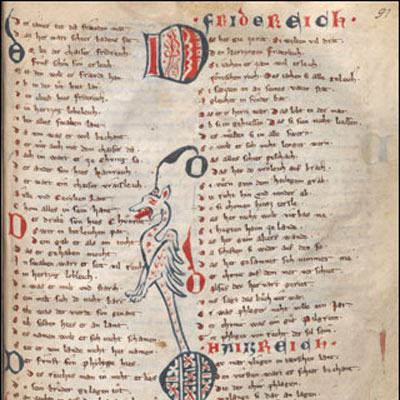

CP. The Kaiserchronik is one of the first proper chronicles written in any European vernacular, and certainly the first in the German vernacular of the time: a form of Bavarian Early Middle High German, used in what is now Bavaria and Austria in the middle of the twelfth century. It survives in a staggering number of fifty manuscripts (not all of them complete), continuing well into the 15th century. This is extraordinary, and suggests a huge interest in this text among audiences from all over the German-speaking world, across a period of almost 400 years. Usually, we would think of the audiences for these vernacular chronicles as lay people or ‘non-specialists’ as you put it: illiterate or at least non-Latin-reading nobles and the wider courtly society around them. Courtly society was, at the time, just in the process of becoming the driving force for cultural patronage and literary production we know from later centuries. However, in case of the Kaiserchronik, there are hints of other surprising audiences, e.g., one manuscript, in a monastic collection, contains a translation of a passage from the Kaiserchronik into Latin. Usually, these things happen the other way round. This suggests that even Latinate monastic audiences found something of interest in the Kaiserchronik.

BB. Is the Kaiserchronik a key document for historians, or does the narrative include a strong element of legend or hagiography that makes it more interesting in terms of cultural or literary studies?

CP. From a modern perspective, the Kaiserchronik is a very bad chronicle indeed: it gets most of its account wrong, mixes things up, skips forwards and backwards through time, amalgamates historical figures who in reality were separated by several hundred years. It also is preoccupied with legends, miracles, saints, hagiography, as you say – not things we would usually expect in a chronicle. However, one of the fascinating things we learn from the Kaiserchronik is that value as a historical source and interest as a literary piece of work are not mutually exclusive. Initially they appear at odds to us as modern readers who approach these texts with expectations shaped by ideas of historical objectivity, veracity and factuality. However, well into the eighteenth century, chronicles were literary pieces of work as much as historiographical treatises, and they had to live up to contemporary audience expectations. Readers, or rather listeners, because we have to imagine these texts being read out loud to a larger audience in a courtly setting, expected to be entertained, educated, and informed, as well as having the values that governed their social, political and religious lives confirmed.

BB. What does the Kaiserchronik show us about how writers experimented with story-telling techniques in the twelfth century?

CP. The episodic structure of the chronicle – it breaks down into fifty-something episodes – allowed the author or compiler of the Kaiserchronik to experiment with different genres, sources, and traditions. Its account is full of chivalric knights, pious saints, emperors both exemplary and tyrannical, miraculous popes, and unruly bishops. At times the Kaiserchronik reads like a Germanic heroic epic, full of bloody battles and sword-swinging heroes who take on whole armies by themselves, and then again it reads more like a Byzantine family drama, with complex plots of family betrayal, separation, confused or hidden identities and finally reunification and reconciliation. For good measure there are also lengthy religious disputations, dragon attacks, shipwrecks, assassinations, daemonic possessions, and pious martyrdoms. It really is a colourful, at times chaotic tableau of wild and fanciful narratives, tied together by a palpable joy of storytelling.

BB. Would you describe the Kaiserchronik as a didactic religious text focusing primarily on the foundation of Christianity in Europe, or is it more interested in the themes of power and kingship?

CP. A bit of both, but mainly the latter. The text does devote a lot of space to narratives about the Christianisation of the Roman Empire. It presents this process as a succession of encounters of Roman emperors with the paragons of early Christianity: Peter clashes with the Emperors Claudius and Nero, Veronica converts Emperor Tiberius, Emperor Decius martyrs Pope Sixtus, and so on, until finally Pope Silvester converts Emperor Constantine and together they commence a programme that entirely recodes the Roman Empire as a Christian Empire. But this focus on Christianisation is only there because it is necessary to explain to a twelfth-century audience how the Roman Empire, which they see themselves as still inhabiting, came to be a Christian entity, when it started out as a pagan one. The main interest of the chronicle here is to reassure its audience of the continuity, stability and authority of the Roman Empire for the medieval German and Christian Empire of the twelfth century.

BB. You are now based at the University of Berne in Switzerland. How did you find the transition?

CP. Yes, I’m now a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellow at the University of Berne, working on a new project on city laments in the later Middle Ages. The transition from the UK to Switzerland wasn’t easy: I loved living and working in the UK, I had great friends and colleagues there, and the privilege of teaching some of the brightest young people I have ever met. Being in dynamic and international places such as Cambridge and later London and Oxford was, for a country boy form Northern Bavaria, an exhilarating and stimulating experience.

Initially we left the UK just at the beginning to the pandemic to be closer to family. My wife and I were both doing postdoctoral work at Oxford and intended to return, but Brexit and the pandemic had made us weary. And then I got a job at the Uni of Bern, which led to the wonderful research position I hold now. So we ended up staying in Switzerland. I love it here, the quality of life is great, the landscape is beautiful, and of course it is great to be closer to family, in particular for our two little kids, who enjoy quality time with their grandparents.

BB. Are there aspects of the UK that you miss?

CP. There are things I miss A LOT about life in the UK: pubs being one of them. I think the UK does pubs really well, and that’s coming from someone who grew up in the German region with the highest density of family-owned breweries and pubs. Also, as a father often out and about with a pram or a bicycle trailer I REALLY miss those green ‘push to open’ buttons on doors. They simply are not a thing in Switzerland, and that can make navigating buildings with a pram/stroller very annoying. If I were to compile a list of the top-five things I miss about the UK, it would be: 1. pubs, 2. green ‘open door’ buttons, 3. speaking English in my everyday-life, 4. being surrounded by English language, literature, music and culture, and last but not least 5. mince pies at Christmas. I am still looking for a way to get them here, so far to no avail.

What I really do NOT miss about the UK is the constant political drama since the Brexit referendum in 2016. Switzerland has its fair share of political problems, but nothing comes close to the erosion of public trust and political culture in the UK exacerbated by the fallout from Brexit. If I were to compile a list of the top-five things I do NOT miss about the UK it would be: 1. Brexit, 2. Brexit. 3. Brexit, 4. separate cold and hot water taps, and 5. Brexit.

BB. Do you ever find time to relax?

CP. Ha! Just recently I managed, after a ten-year hiatus due to university, work, and later the kids, to start playing Dungeons & Dragons again. I’m only now realising how much I missed a creative outlet like that. It’s also satisfyingly medieval, not just because it contains swords, dragons, ancient ruins and adventure, but the whole thing is basically an oral impromptu quasi-performance for the purpose of collaborative storytelling, which strikes me as tremendously medieval!

full news feed • subscribe via RSS