The Kinsman's Version

Barbara Burns talks to Massimiliano Morini, whose edition The First English Pastor Fido (1602) has just been published in the MHRA Tudor and Stuart Translations series.

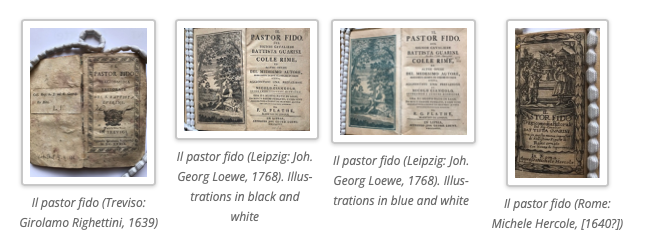

BB. The focus of your study is Giovanni Battista Guarini’s pastoral tragicomedy Il pastor fido, an influential text of the late European Renaissance that circulated in many versions and languages throughout Europe for more than a century after its first publication in 1589. The work also inspired composers of madrigals, and some of our readers may know Handel’s operatic version. What was it about this text that made it so fashionable and innovative?

MM. It is difficult to explain this to audiences today, because this kind of play (with a complicated plot involving a divine curse which can only be resolved when two youths of divine descent unite in marriage, as well as a case of mistaken identity which almost leads to tragedy but is resolved before the happy ending) does not generally appeal to post-Romantic sensibilities. The fact that the Italian play is very long, and written in formal, ‘literary’ verse, also doesn’t help. But the audiences of the latter half of the sixteenth century were really fascinated by this play which mixes a serious, religious Graeco-Christian plot with amorous dalliance, and above all (as we can only guess) by a mixture of acting, elaborate scenography, music, singing and dancing that anticipates opera (see Handel).

Of course, when I refer to these sixteenth-century audiences, I actually mean courtly audiences, because this was the sort of entertainment that was calculated to please Princes and Princesses. Though it has to be said Pastor fido was so complicated that it was staged only a handful of times, and it was more of a literary than a theatrical success.

BB. Your book is an edition of the first English translation of the play, published in 1602. What can you tell us about the translator, his motivations, and his creative achievement?

MM. Well, in fact we are not even sure of the translator’s identity. We only know that he is a ‘kinsman’ of Sir Edward Dymock, Champion of the Queen (a ceremonial role). I follow another scholar’s attribution in identifying him as Tailboys Dymock (Edward’s younger brother), who was known for writing some satirical poems and a slanderous play. So his motivation (or the motivation of the playwright Samuel Daniel and the other people involved) was probably pleasing Edward Dymock. His achievement, however, is very interesting: he is not necessarily a great Italian scholar, but he seems to have a clear idea of what he wants to create, which is an English play, more compact than the source and largely (though not entirely) written in blank verse.

BB. You describe this text, tongue in cheek, as a ‘forgotten English translation of an outmoded Italian original’. So why is it meaningful to study it today? Did it influence other playrights, or what do we learn from it?

MM. It’s worth examining because it is not only (largely) written as if it was an English play, it is also presented as one: Guarini’s prologue is omitted, and the play was printed by one of the stationers who had started investing in play texts in the 1590s (before that decade, plays were not considered profitable as printing material). So, while it would be a bit fanciful to claim that this translation influenced English playwrights, it makes sense to say that it gives us a fair idea of what an English translator, an English printer etc. considered to be the right language and the right format for an English play. As I am a translator historian/theorist, to me this is a very important document in the history of ideas about translation, about theatre/drama translation, and about theatre/drama translation in Britain.

BB. How did you get interested in Renaissance drama and translation?

MM. It all goes back to my PhD (at Florence, in English and American Studies), when I realized that there were historical and theoretical gaps to be filled in the study of early modern translation. I wrote my thesis on that, it became my book Tudor Translation in Theory and Practice (Ashgate, 2006). That book in its small way exercised an influence, and I’ve been following strands of research in this field, off and on, ever since. Plus, I’m a translator, and the way another translating mind works will never cease to fascinate me.

BB. What were the ups and downs of tackling this project?

MM. The rewarding thing was discovering that actually, as I’d hoped, this edition helped me to understand and define a number of things which were still a little obscure, in the field of early modern English translation (unless I’m deluding myself, of course). The challenging part was working as a philologist, which is not who I am. I am somebody who likes to build big theoretical buildings, rather than look at some minute point of spelling or historical semantics. But that was exactly the reason why I chose to do it. I wanted to prescribe myself something that was not my cup of tea, because I believe that we only grow (if that doesn’t sound too pretentious) when we do that. And of course it helped that the MHRA Tudor and Stuart series is mostly interested in presenting readable versions to a modern audience.

BB. You teach English Linguistics and Translation at the University of Urbino, and you’ve recently published a book on translating theatre. Does literary translation feature in the student curriculum, and is this a popular field of study?

MM. In Italy there are a sizeable number of courses on translation/interpretation/mediation, so this has been a vibrant field for some time. I’m not sure it will remain that vibrant because of developments in AI which appear to mean that we will still need professional translators for complex things, but only people able to correct Google Translate for smaller, more menial jobs. At Urbino, what we have is literary curricula with a sprinkle of translation practice/theory here and there.

BB. Do you do translation work yourself? If so, which genres or eras are you interested in?

MM. I do, yes. For a few years (2004-2010), I worked as a literary translator of contemporary novels/stories/essays for national publishers, which meant that sometimes I was asked to work on wonderful stuff (Les Murray’s Fredy Neptune, Claire Keegan’s two collections of short stories), and sometimes I had to plod my way through some quite uninspiring material (the odd ‘professional’ writing-course American novel). Then for a few years I only translated what came my way and seemed worth it either in literary terms (Much Ado about Nothing) or in terms of money/prestige (a history of contemporary music for the publisher Einaudi, for example).

During lockdown I decided to re-read all of Chaucer and translated the prologues and epilogues of the Canterbury Tales in Italian hendecasyllables. To my amazement, the publisher Feltrinelli accepted the manuscript, and that book is now out. Now I’m finishing Great Expectations (Feltrinelli again), and I hope to do more stuff for them. Poetry or prose, I don’t mind, as long as it’s good and it doesn’t predate Chaucer (I wouldn’t trust myself with Old English). My dream – if one is allowed to mention something that has no bearing whatsoever on the topic under discussion – is translating George Eliot’s Middlemarch.

full news feed • subscribe via RSS