Peter Haidu and Me

The Philomena of Chrétien the Jew: The Semiotics of Evil (Research Monographs in French Studies 59), by the great medievalist Peter Haidu, was a posthumous work. Here, his editor Matilda Bruckner looks back over their long friendship.

I met Peter Haidu in 1968 during my first year as a PhD student in French at Yale. He was giving a course on the romances of Chrétien de Troyes—an appropriate starting point for a relationship that evolved from teacher and student, to dissertation advisor and advisee, and finally to mentor and friend, but always threaded through our mutual engagement with the work of the great twelfth-century romancer who invented Arthurian romance and some of the most fascinating stories of medieval Europe still vibrant in the modern age, whether Lancelot’s love for Queen Guenevere or the quest for the Grail. Ironically, I didn’t actually sign up for Peter’s course since I didn’t yet read Old French. As an auditor in what was for me an extra sixth course, I had to drop out before the end of the semester. But the following year I was able to take Peter’s course on thirteenth century romance, and his response to my final paper on the use of repetition and variation was enthusiastic. The topic anticipated in some ways what would eventually become the subject of my dissertation but at that point, as a devotee of Flaubert, I was intending to become a dix-neuviémiste.

The following year, 1970-71, Peter was in France on a Morse Fellowship (a perk of his Yale position as Assistant Professor), and I was mostly in Brooklyn, where I lived after marrying in the summer of 1969, commuting to New Haven periodically as I studied for my qualifying exams. It was only after those exams that I had a conversation with Peter in which he encouraged me to become a medievalist: by that time the “PhD glut” had become evident, the 19th century field crowded, and—as Peter put it—there was less competition and a real need for good medievalists. At the worst, he told me, you might spend a few years driving a taxicab. Luckily, I never had to resort to that diversion but I certainly didn’t realize when I decided to take his advice—I did really enjoy reading those romances!—that the number of jobs for medievalists in French was quite limited and the requirements of the field steep. But I’ve never regretted accepting Peter’s invitation to work with him in a field that offers a broad spectrum of possibilities ranging over centuries of French literature and its interdisciplinary connections.

Peter left Yale for the University of Virginia and then the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign before I finished my dissertation. We were rarely in the some place and conducted our exchanges mostly by mail in those days before the Internet. I remember with great fondness the trip my husband and I made to Charlottesville to discuss my first chapter with Peter. I can still see in my mind’s eye baby Noah sitting in a high chair, his little round face looking on with the concentrated expression of a wrinkled old man, as we watched Peter’s wife make croissants from scratch, rolling together dough and butter over and over again. The highlight of our trip to meet with him in Illinois was Peter taking us to the Art Institute in Chicago, the beginning of my lifelong love for that fabulous museum. But at the heart of those visits was of course our intellectual engagement: as he and I went over Peter’s many marginal annotations on my writing, he gave me more bibliographical resources, hard questions to think about, warm encouragement to continue to dig deeper, analyze the texts more fully. Peter’s greatest gift to me in that process was his respect for my work, my abilities, my ownership of the project in which he recognized me as the one who made the final choices and knew the most on the topic at stake. He never tried to make me into a disciple to fit into his mold, as many mentors do.

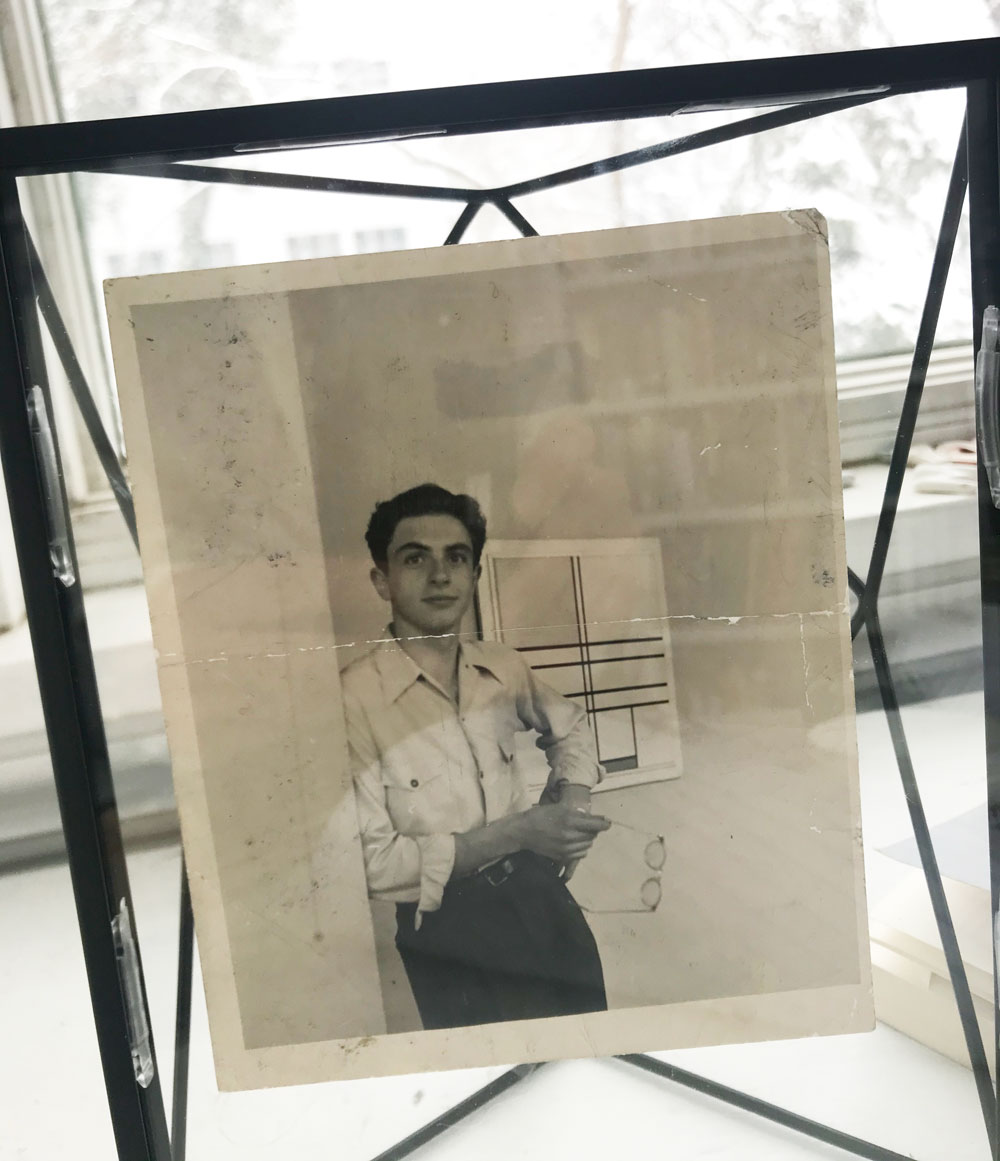

Peter’s faith in me and my work, the freedom he gave me, has continued to guide and sustain me throughout my career, even when he clearly disagreed with my approach to Chrétien’s last, unfinished romance: where mothers and sons played a role, we each had our own views of a work known as the Perceval (featured in Peter’s first book on aesthetic distance) but named by the author as Li contes del graal. The unattainable grail has been the source of much rewriting and reconceptualizing over the centuries, and Peter and I—the son of a particular mother and me a particular mother of sons—definitely had different views! His mother Henia’s friend, a professional photographer who introduced Peter to photography, took the photograph of a handsome young Haidu you can see along with these reflections. The somewhat skeptical but amused expression on his face, the casually held glasses, and the Mondrian print in the background give a good indication of the man “tel qu’en lui-même” who excelled in the world of intellect and art.

Over the years Peter and I met in a variety of places: I invited him for a lecture at Princeton and later at Boston College; he invited me to lecture at UCLA and introduced me to the Getty Museum; I visited him in Paris and Brooklyn. But mostly our intellectual and personal friendship was carried on at a distance, virtual but vital, as we exchanged work back and forth, getting and giving feedback, helping each other refine ideas and clarify expression. I know that for others in the profession Peter was not always easy to get along with (most of the UCLA French Department, apparently unwilling to support a colleague with whom they quarreled, were no-shows at my lecture there). In print, Peter didn’t pull his punches against scholars with whom he disagreed. He once told me that he didn’t learn Hungarian, his mother’s native tongue, since his mind was already complicated enough.

After his death in 2017, I went to New York for the memorial concert his son Noah gave at Birdland and then met Peter’s daughter Rachel at his apartment in Brooklyn to look at his computer and papers. We found a confusing multiplicity: many copies of chapters and little indication of the final state of the manuscript he’d sent out to a publisher. As I’ve explained in the introduction, once I obtained those 500-600 pages, I set to work editing them in relation to the copy I had from the series of exchanges Peter and I had in 2016 when he sent me a copy of the book along with a request for comments. I knew it was not going to be possible to publish the whole manuscript (despite Peter’s ardent desire) but felt certain that the extraordinary analysis of Philomena in light of the Jewish massacres of 1096 had to find a publisher. Rachel and Noah gave me carte blanche to do what I thought best.

At first I found it very difficult to change anything in Peter’s writing, aside from obvious moments of inattention or repetitive diatribes against a variety of targets. How could I touch the work of my mentor? But as I read and reread, trying to penetrate the logic of his argument and its multifaceted implications, I gradually found it easier to intervene in order to serve what I understood to be the best of his thought and the power of his insights. Some details of the process and the effects of my editing, laid out in my introduction, indicate the extent to which I reshaped Peter’s manuscript to midwife The Philomena of Chrétien the Jew: The Semiotics of Evil. I believe it remains Peter’s book, quintessential Haidu, a book I could never have written myself, but a book that I had to make my own for it to reach its public in his impassioned voice.

Peter Haidu was a brilliant, intense critic and scholar, politically engaged through his writing, as conversant in the fields of history and literary theory as in that of medieval French literature and philosophy. I wish he could see what our collaboration through his ground-breaking Semiotics of Evil has produced!

— Matilda Tomaryn Bruckner, April 2021

full news feed • subscribe via RSS